I’ve never been to Mercedes-Benz’s museum in Stuttgart, but I’ve been told that visitors are greeted by a stuffed horse standing next to the words “I believe in the horse. The automobile is only a passing phenomenon” at its entrance.

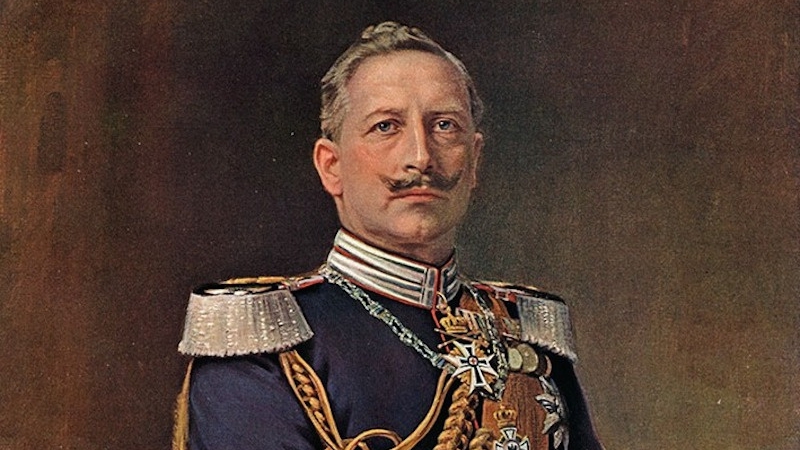

Those words were uttered in 1905 by Kaiser Wilhelm II, the last emperor of Germany, and he must have thought that the world would continue its dependence on the horse as they have been for the past six millennia. But he was wrong. Cars are still here today, and the German aristocracy isn’t.

Not to berate his lack of foresight, even though this was the man who went on vacation while the whole of Europe was loading themselves into a hell-bound handbasket during the Sarajevo crisis, he wasn’t alone in thinking that the car wouldn’t amount to much in the grand scheme of things.

Though there were plenty of “automobile manufacturers” back in the early-1900s, these manufacturers were more like small, fragmented enterprises tinkering with the wonders of internal combustion powered chariots and not the multinational conglomerates we recognise them as today.

Don’t think of them as Toyota or even Rolls-Royce. Think of them as the Christian von Koenigsegg and Elon Musk of the steam era, building interesting small-volume horseless carriages that only the curiously wealthy could afford. But even back then, a major player like Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft, formed by the inventors of the automobile, believed that the global market for these automobiles wouldn’t exceed a million as there wouldn’t be enough qualified chauffeurs to drive them.

In addition to that, being of the aristocracy, the Kaiser had an obvious bias towards horses. After all, he is part of an establishment rich enough to employ a specialised workforce in tending to the whole business of breeding, raising, training, and maintaining a stable of the finest steeds.

As for the peasantry, they had to make do with lesser mules and draught horses, many of which weren’t majestic beasts of speed and grace, but stubborn and uncouth beasts of burden whose lives were destined to be nasty, brutish, and short by most accounts.

But not like the peasants could afford anything else. Automobiles were eye-wateringly expensive and, by today’s standards, hopelessly difficult to operate. It is likely that the horse could have continued to dominate civilisation’s main mode of transportation for another century if it wasn’t for something known as the First World War.

Even though WWI was popularised as the first mechanised war, as it debuted the use of aerial bombardments and tanks, much of the mobilisation of troops, artillery, and supplies were carried out by horses, hundreds and thousands of them who were drafted into the military and shipped off to the front lines alongside the many youths who were sent to fight it.

As helpful as the horses were in delivering vital aid and munitions, where train tracks couldn’t reach nor the rudimentary trucks of the period could traverse, they too were being maimed and gunned down in the conflict. Like the many infantrymen in the trenches, horses weren’t easily replaceable. You can’t simply order a new batch of horses from home but hope that farmer Tom’s randy stallion had been extra productive last spring.

With that said, beneath its grotesque visage, war is a great driver of innovation, and the escalating conflict on the Western front caused an increased demand in automobile manufacturing as governments started purchasing motorised trucks to aid in war logistics. This influx of government funds, in turn, grew these otherwise tiny cottage industries into a sizeable manufacturing operation, some of which churned out thousands of trucks to support the war effort.

Soon enough soldiers were supported by numerous trucks and buses that didn’t need vast amounts of food to run and wouldn’t be so easily put out of commission by gunfire or traps.

Unfortunately for the horse, their fortunes didn’t change when the war ended. While infantry, machinery, and weapons got a free ride back to their homelands the military didn’t care much for the horses.

Deemed too costly to be transported back, the top brass only picked the finest to bring back to be paraded as war victors, while the vast majority of horses were left behind with many being butchered for food to feed the surviving civilians, or sold to them to be put back into work in an effort to revive their destroyed economies.

This vacuum of able workhorses in the economy, coupled with the sudden widespread availability of motorised transport in society, inevitably changed the dynamics of logistics in the post-war era. While nations were busily replenishing their supply of horses, through the age-old method of breeding, raising, and training them, automobile manufacturers had no such limitations and could quickly supply a batch of motorised transport ready for service at a comparatively rapid pace.

Furthermore, motorised transport was far more convenient to produce and maintain than your average equine worker. For starters, the average factory worker didn’t need generations of handed-down knowledge to learn how to train and groom a sentient being for civil life. All they needed to know was which way the assembly line moved, what two things they need to put together, and “righty-tighty, lefty-loosey”.

Furthermore, motorised transport was far more convenient to produce and maintain than your average equine worker. For starters, the average factory worker didn’t need generations of handed-down knowledge to learn how to train and groom a sentient being for civil life. All they needed to know was which way the assembly line moved, what two things they need to put together, and “righty-tighty, lefty-loosey”.

As for its operation and maintenance, the motor was far easier to manage as one could easily figure their way around an internal combustion engine in the span of a month, rather than years of carefully observing the behaviour and nature of horses. Engine blew a gasket? No problem, pull out your tools. Horse broke its leg? Too bad, get the musket.

In this world of growing economies of scale and rapidly improving technology, the horse simply could not compete in terms of ability and convenience. It is no surprise that the English and French horse population is said to have peaked in 1920, shortly after hostilities in Europe ceased. Horses would be summoned to duty once again by the resource-strapped Germans in World War 2, but by then the tide had changed, and the horse would never return to a position of prominence.

Today the role of horses has been greatly diminished to that of high society events or providing leisurely rides and activities for tourists. Roles, which rather ironically, Bob Lutz points out as the fate of all cars in the near future. Playthings of the idle rich only to be paraded out at high society events like Goodwood, Pebble Beach, and most likely due to its historical significance and circumstance as a civilian motorway, Circuit de la Sarthe at the town of Le Mans.

After all, the origins of our infatuation with the car are no different from that of the horse. We may laugh at the thought of how does one love or admire such a daft and temperamental animal, but a 19th-century horse owner might think we are all stark raving mad for our obsession over cold unfeeling machines. It doesn’t make sense for an assembly of bolts and gunmetal to have a soul of that of a breathing creature with a beating heart of naturally formed flesh.

There are plenty of parallels to draw between the demise of the horse and the car. For one, you cannot deny the sheer convenience and economic sense of an autonomous car. Even though such technology is exclusive and expensive as the first motor cars were at the turn of the 20th century, we forget just how quickly technology advances, and within the span of a decade the technology has refined itself far better than many had anticipated. Furthermore, it is quickly filtering their way down into mass market, bread-and-butter offerings at an equally rapid rate.

Even if you disregard the chorus of anti-autonomous car commentators who comment with the frothing fury of an NRA member over gun control, as of now, autonomous cars might have a slower than expected uptake as consumers are still distrustful over its effectiveness. Manufacturers, legislators, and customers are still divided over the many possible legal and moral ramifications autonomous cars would bring should it fail to avoid a hazard.

The hot question isn’t whether autonomous cars would take away our freedom, but whether anybody would be willing to give it up in the first place.

And this is where we have to draw another parallel to the demise of the horse. For such a change to happen, there needs to be a world-changing event to get everyone out of their cars just as the First World War got everyone off their horses. The thing is, that world-changing event had already taken place and its cogs have been turning since the collapse of the Soviet Union.

* * *

This is the second part of the four-part series titled Our Autonomous Future. Read on with Part 1, Part 3, and Epilogue.