Recently, lamentations were heard coming from motoring enthusiast sites in The States over Audi USA’s decision to drop the last manual option from their line-up. At this point should we be surprised that a brand that once gifted the world the R8’s open shifter is devoid of manuals or should we be more surprised that they had manuals in this day and age at all?

Contrary to the groans of discontentment from vocal enthusiast circles, the passing of yet another manual option slips by without so much of a whimper from the silent majority. Why should they feel otherwise?

There was a time not too long ago when the automatic option costed a significant premium, but with little to no price difference nowadays – with the exception of specifying a manual would likely mean ordering one from the factory with no dealer discounts – the vast majority of customers see little reason to opt for the DIY option.

Enthusiasts will always rise to the defence of manuals for its esoteric qualities. A good manual shift is one of those invigorating life-affirming aspects of driving, a bond that only a true petrolhead will understand.

That simple act of disengaging the clutch, blipping the throttle, and guiding the gear lever through to the next slot at the flick of a wrist is like a firm and encouraging handshake – or more like a Masonic handshake by the aptitude of the average driver today.

Thing is, the shift in preference has less to do with a switch in customer mindset. As features such as air conditioning, to powered windows, and power steering had proliferated through the market over time to become the expected norm nowadays, the one constant that had precipitated such changes is the customers’ demand for more convenience, and the growing preference for automatics over manuals has more to do with the evolution of powertrain technology in the last 20 years.

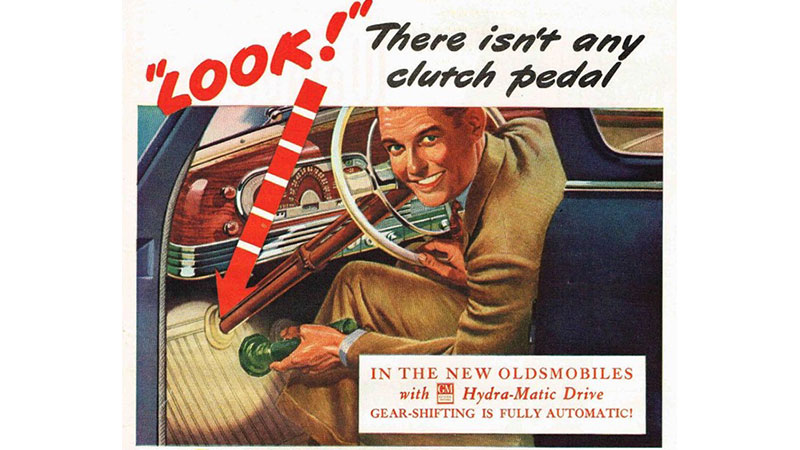

The torque converter automatic transmission that we know of today was brought into the world by the Americans in the 1940s, but for more than a half a century the transmission was mainly the reserve of the higher-end of the car market.

Even well into the 1980s, the automatic transmission was still a very expensive option, with customers preferring to have other onboard luxuries such as air-conditioning and velour seats rather than a self-shifting box.

Of course, back then there was a good reason to pick the manual over the dull and lurchy automatics. On top of it being cheaper, it was also more fuel efficient and easier to maintain.

But as it is with many revolutions in the story of the car, the beginning of the end for manuals was initiated by environmental and economic factors.

Just as how the Arab oil embargo and the American Clean Air Act opened the doors for Japanese manufacturers to step into the crucial North American market, the soaring fuel prices from market speculation and Al Gore’s scary polar melty fun time videos of the early-2000s changed the game yet again. This time, instead of more fuel-efficient pauper-spec econoboxes, engineers started to go down a different route altogether.

As governments focused more on emissions and with little indication of fuel prices easing, diesel engines offered a novel solution – easy low-end torque. Its higher torque output, broad spread, and low-end delivery made it a boon to fuel consumption testing standards, even if – to the horror of many environmentalists later – it produced copious amounts of noxious gases that few countermeasures could really remedy in the long term.

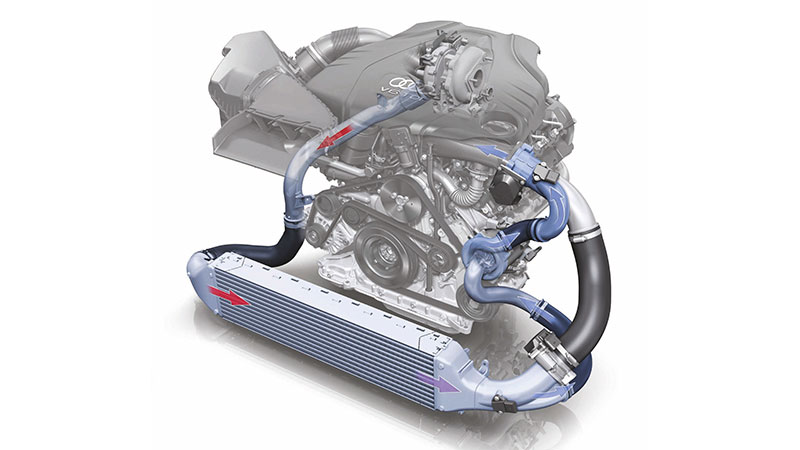

Taking a cue from the oil burners, engines were quickly downsized and fitted with tiny turbochargers that were tailored to deliver more torque and earlier in the rev range, whereas more gears were added and ratios reduced to expand the capabilities of an automatic transmission.

With peak torque now served up from as low as 1800rpm, there is now little point to hold onto the gear and push further up the rev range to dole out more power – not unless you are really gunning in search of that peak power high in the relatively far reaches of the rev range.

Naturally-aspirated engines of yesteryears had their peak torque in the middle of the rev range – usually around 4000rpm. So if you wanted to wring some power out of the engine and make some decent progress, you had to hold onto the gears. Similarly, turbocharged performance engines tend to use large turbochargers to deliver a bigger boost and a higher peak power, with the obvious trade-off being copious amounts of turbo-lag.

In the past, it was this torque progression that made manuals far superior to their slushbox counterparts. By shifting cogs yourself you could not only decide to hold off a gearshift in order to reach the meat of the powerband but you to could switch gears quicker than an auto and maintain engine speeds to keep that momentum going.

However, with most modern turbocharged engines dispensing peak torque just over the tick over and maintaining a broad powerband all the way through much of the engine’s rev range, there isn’t much reason – or reward – to hold off a shift and keep climbing up the powerband.

One of the first cars that demonstrated this anomalous behaviour was the original Peugeot 208 GTi, which had a 1.6-litre engine that punted out peak torque at just 1750rpm. While you could keep fizzing up the engine to 5800rpm to squeeze out its peak power, there was little reason to go past 2000rpm in day-to-day driving.

Furthermore, the gearing was so short that you could short-shift or skip a gear and the engine will just carry on regardless. At speeds below 120km/h, the constantly having to row the gears on the 208 GTi’s slick shifter felt more like a chore, something that could be better delegated to an automatic.

Conversely, the hot Pug’s key rival, the Ford Fiesta ST didn’t have this issue as its engine had a progression of torque, its peak found at the 3500rpm mark, which ideally suited its manual. Renault Sport’s 2-litre turbocharged engine in the Megane RS’ also had a similarly high peak torque point at 3000rpm, which also made for a great pairing with its manual-shifter.

While high-torque outputs might make manuals outmoded, credit has to be given to the rapid development of gearbox technology in the last two decades in response to tightening requirements on emissions.

With more precise sensors and powerful control units becoming available, software engineers could load automatic transmission control units with scores of computer maps to ensure that it is able to keep the engine at peak efficiency in every driving condition imaginable, making it vastly more flexible than the automatics of the previous century.

This meant that engineers could, not only further fine-tune an automatic-equipped car – despite its weight disadvantages and mechanical inefficiencies – to return better fuel consumption figures ratings than a manual-equipped car could hope to deliver, they could also make it react faster and more intuitively to driver inputs. Paired with advancements in the torque converter and clutch designs that closely able to match the shift feel and response of a manual, and it seems that the only thing the average manual driver of today would miss is the use of their right leg.

Make no mistake, there are a few cars that still make the best out of manuals, namely cars with low-torque non-turbocharged high-revving powerplants like the Mazda MX-5 and the Toyota 86, which still feel more suited for a manual gearbox – though it is no coincidence that both cars were designed from the offset to replicate a bygone era of motoring when automatics were lazy and engines were more spirited.

Truth is, the accessible and copious torque delivery from today’s crop of engines comes too hard and too fast that putting things on momentary pause to take your hands off to shift a manual yourself almost handicaps the intensity of its delivery, turning the engine’s effortless nature into a tiresome ordeal that would be better left to the servitude of a self-shifter. Considering that a broader scope of drivers appreciates accessible high torque outputs in the real world over the high-revving and peaky power delivery expounded in – often loutish – marketing materials, there is little chance of manuals making a comeback.

As much as enthusiasts would expound the virtuous traditions of the manual gearbox, the industry is already eulogising its passing as it inexorably slips away into irrelevance in a world that has irreversibly changed with a market that ultimately seeks not the preservation of the sacred but the fulfilment of a desire, and customer desire convenience. That is just how it has always been.