Whether it is the colourful retrofuturism of the Jetsons or the dystopian nihilism of Blade Runner, there is one common element shared between both fictional works – aside from robots with biological sex characteristics – and that is flying cars. Ever since we figured out heavier-than-air flight, science-fiction writers and futurists have always imagined a form of transportation in a future where we would be too damned enlightened for our pompous rears to touch the ground.

However if you find yourself reading this on a bus that is stuck in the gridlock because a handful of commuters forgot how roads work, you’d know that we are still a long way from living the dream. Though, it must be said, this predicament isn’t for the lack of entrepreneurial attempt. The Henry Ford extraordinaire himself had a swing at it, and so did several enthusiasts throughout the 1990s who had a try at it, with all of their work materialising as nothing more than the vaporous product of a vapid imagination.

Clearly the challenge of realising personal airborne transportation is one that cannot be succeeded by lone garage geniuses. Such an undertaking would need capital, massive amounts of it, which is why significant buzz was created when giant multinational conglomerates such as Audi, Boeing, and Uber thought they ought to have a crack at it. And why not? It seems about the right time for flying cars to save urban populations from themselves as cities are expected to become even more crowded and wealthy, and these new players have millions to burn with the means of actually building it.

Adding to that, the concepts proposed by these companies aren’t the sort you find on the back of a dinner napkin scrawled in crayons, with a whole smorgasbord of completely feasible concepts ranging from the plane-copter hybrid of Uber’s ‘flying taxis’ to the sleek shape of Aston Martin’s Volante Vision concept. If there is one thing in common between all these concepts, beside boasting the capability of flight and some level of autonomous operation, is that no one can agree on how users are to board and disembark it.

Uber envisions passengers hailing a ride from specialised platforms known as veriports. Audi and Airbus joint partnership on the other hand built a scaled-up quadcopter drone that carries a two-passenger pod which can be dismounted onto a four wheeled chassis that will continue the rest of the journey. Whereas Aston Martin’s only concern is whether their flying creation will travel higher and faster than the dirty peasants in those flying Ubers, presumably.

Some of these companies are already laying the groundwork for flying cars to start taking to the skies. Uber has signed a Space Act Agreement with NASA to develop an air-traffic control system for their flying taxis, while Audi’s hometown of Ingolstadt has agreed to allow the company to test its flying vehicles over the city.

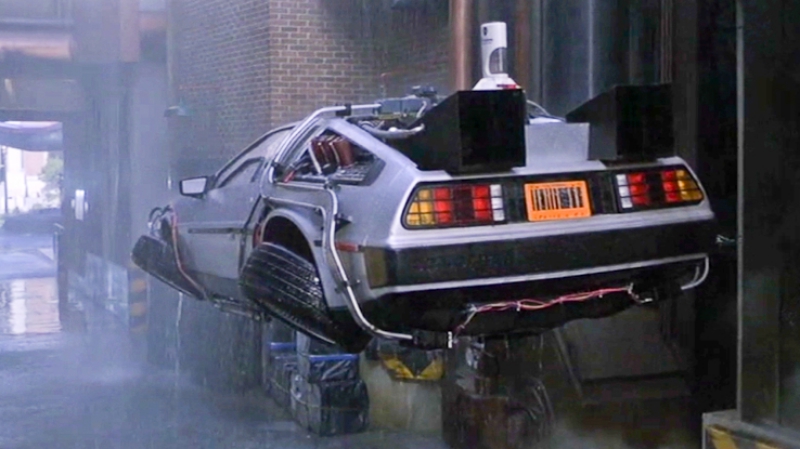

Now before you destroy your driveway and level your roof for a rooftop landing pad in breathless anticipation of the great flying car revolution here is a reality check. The “flying car” buzzword being thrown about is a misnomer, they aren’t cars with the ability to fly by means of some yet-to-be-discovered physics-bending machinations like the hovering cars of Back to the Future II. Instead, these “flying cars” are closer in design to a super-sized version of the drones you see at concerts or a downsized V-22 Osprey you see in your latest Michael Bay flick. Regardless of how the end result appears, these flying car concepts merely a glorified compact helicopter, with all the accompanying drawbacks of having a compact helicopter in your backyard.

While a helicopter ride sounds as exciting and glamorous as dating a supermodel, the reality is broadly similar, in that it is way less practical and impressive than it sounds. If you have ever had the opportunity/misfortune of being next to a helicopter at take off you would be well aware that they do make quite the racket and not to mention the rotor wash it generates just by landing, taking off or hovering above the general vicinity.

If you thought that your neighbour’s straight-piped Civic was obnoxious, it’s positively pious next to a helicopter. Designers reason that the use of several small electric driven rotors – rather than one whacking big fan powered by a turbojet – would significantly alleviate these issues, though not completely eliminate them.

That being said, using electric propulsion presents flying cars with a Catch-22 situation. Since many of these flying cars require VTOL (vertical take-off and landing) capabilities and are unable to have broad wingspans in order to navigate crowded urban areas, a huge amount of energy would be spent just keeping itself in the air.

This, of course, means the flying cars would need more batteries, which in turn means more weight, which can only be countered with the use of more batteries, ad infinitum. Furthermore, in a real-world operating scenario, the flying car would need extra energy to carry passenger loads, as well as overcome headwinds and bad weather conditions.

With many futurists and companies boldly proclaiming that we will have flying cars within the next decade, those predictions seem to be a tad optimistic in light of the technical and bureaucratic challenges that still lie ahead. Even perpetual-innovator Elon Musk himself said back in 2017 that it was “difficult to imagine the flying car becoming a scalable solution”, instead choosing to focus his attention on boring underground tunnels in California as a more cost-effective solution of avoiding congestion.

Though it should be noted that Musk seemingly changed his tune recently with a suggestion that the “SpaceX package” on the upcoming Tesla Roadster will feature miniature thrusters that will “even allow it to fly”. Though the statement was posted on Twitter, which everyone knows is the bastion of truth and objectivity in 2019.

Perpetual-funding seeker Musk’s Twitter tease/satirical take does provide an answer to all the latest mania surrounding flying cars. As previously discussed regarding the craze of autonomous technology, the pursuit of putting cars in the air – so to speak – does mirror some of the irrational stock market mania surrounding new “disruptive” technology such as cryptocurrency and artificial intelligence.

The lack of solid plans for commercialisation, claims of “disrupting an industry”, and the vague plans for profits smacks of companies trying to lure curious investors and venture capitalists with the hope of getting in early on a share of striking “The Next Big Thing”, which isn’t to say that it is entirely disingenuous.

Many, if not all great innovations in world history are founded by a visionary who is funded by optimistic investors who are looking for ‘The Next Big Thing’, be it capitalists, governments or royalty. It doesn’t matter if the reality of flying cars doesn’t live up to dreamy expectations, or more pertinently, doesn’t make bank, in the end. Because the core truth is that we all want to buy into the dream, and hopefully the ones with the deep enough pockets believe in that tangible dream long enough to bankroll it into a reality, even if the reality isn’t what many had in mind.