There are a lot of things car enthusiasts can’t agree with. Torque or horsepower, petrol or electric, SUV or sedans. You get the idea. Yet, when it comes to naming the most beautiful car of all time, common folk, industry veterans, and fart-sniffing connoisseurs can all agree on nominating the Lamborghini Miura.

They say beauty is subjective, but heavens above did Bertone’s Marcello Gandini prove that statement wrong with the Miura. Whether you like classic cars or think it is an anachronism, there is something hypnotic – even divine – about its looks.

If the legend that Gandini finished its design within days of its unveiling is true, then it is truly a gift for the ages. It has been 55 years since its first full-bodied appearance, yet it looks as though it hasn’t aged a day. And what a fitting bookend of an era in automotive design. Wait. What?

Was the Lamborghini Miura the first ‘supercar’?

For all the hype it generated over its mid-engine layout, even inspiring the late great LJK Setright to coin the word ‘supercar’, the Lamborghini Miura didn’t start anything. By the time Lamborghini’s legend made its debut, mid-engine cars weren’t new, nor was the ‘supercar’ term. The latter of which will be something for enthusiasts to debate over.

That said, I don’t doubt Steright’s erudition. Nobody writes wistful tributes to a bygone automotive writer after all. Then again, once described as an ‘Old Testament prophet in Savile Row clothes’, Setright might have been a step ahead of his time. But I’ll get to that later.

In the meantime, it is worth explaining why the Lamborghini Miura wasn’t Genesis, but the epilogue of pre-war car design. And you don’t need to crack out the shovel and dig deep into the rabbit hole that is art history for answers. The proof is right there, in the car’s profile.

Look at those long flowing front flanks. That swept-back cabin, which tapers off into a perky rear. Gorgeous, but also, very un-supercar-like to the examples we know today. It is almost as though it is an antithesis to nearly every supercar that came after. That is because the Lamborghini Miura more closely resembled past grand tourers than its future mid-engine descendants.

Designed by engineering

How the Miura ended up this way had less to do with the era from which it came, and more to do with its engineering. See, the Miura’s chief engineering, Gian Paolo Dallara, wanted to build a compact mid-engined road car. Something similar to the Ford GT40 and the mid-engine Ferrari prototypes that duked it out at Le Mans.

Initial designs for the Miura proposed a three-seater layout with a central driving position and a longitudinal engine. Much like Gordon Murray’s vision for the McLaren F1 two decades later.

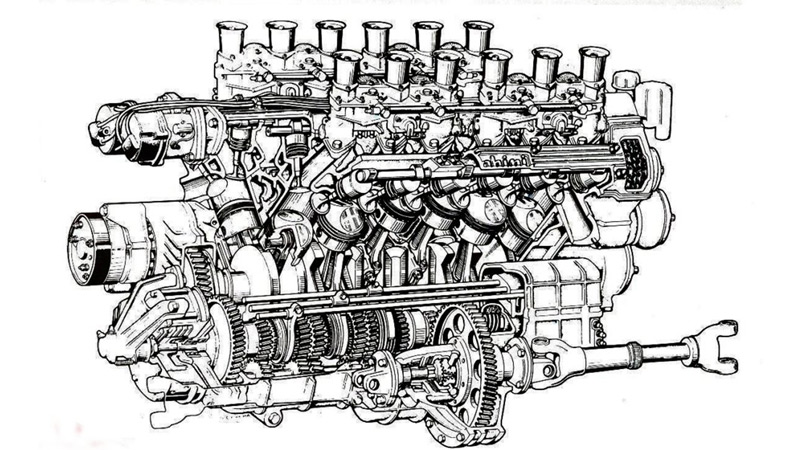

However, Dallara thought that fitting the engine lengthways made the car too long and messed its weight distribution. Instead, he flipped the 53cm-wide Bizzarrini-designed V12 transversely, squeezing it between the firewall and the rear axle.

Of course, you never hear the word ‘transversely mounted’ when it comes to supercars. And for a good reason. The layout simply doesn’t make for a very efficient mid-engine package. Forget the occasional service. Even getting the power to the rear wheels proved to be tricky.

The Miura’s unique engine layout

To get around the Miura’s tight engine bay space, Lamborghini took inspiration from the BMC Mini’s gearbox. Rather than attaching a separate gearbox to the end of the engine’s crankshaft, Lamborghini’s engineers integrated it into the side of the engine block.

This meant that it shares the same engine oil sump, like a motorcycle. Not a good idea in execution. If you were to crunch its gears, you can expect those bits of metal to find their way into the high-revving V12 engine.

Not only that, because of the drivetrain packaging, the Miura’s weight distribution was slightly rear-biased. With its front fuel tanks brimmed, it boasted a 44.5/55.5 front/rear weight distribution. A ratio that would slide backwards as the tanks drained. Charming.

Nevertheless, Lamborghini was excited to show the public what they were working on. Even before Gandini had a chance to clothe it, the Miura’s bare chassis – with its engine – appeared at the 1965 Turin Salon.

For many show-goers, it certainly wasn’t the first mid-engine car they have ever set eyes upon. But it was the first mid-engine production road car, and one with an exquisite V12 engine. It was only the bones of a car, but it was enough to convince some to commit, with Lamborghini receiving ten orders at the show.

Inspired by its past peers

With the chassis ready and orders in hand, Gandini got on with tailoring a body. And what he ended up with resembled the contemporary beauties of its era. Its sleek profile echoes the shapes of other grand tourers like the Jaguar E-Type and Ferrari 250GT Lusso. If one were to guess, the Miura looked like it was packing a front-mounted engine.

It is uncertain if its initial concept for a longitudinally-mounted V12 would have resulted in a different looking car. However, one wouldn’t need to flex their imagination to visualise how it might have ended up. Just look at Gandini’s next Lamborghini commission, the Countach.

The Countach, where the future is heading

Wedge-shaped, cab-forward, with a body that is more sex symbol than sexy sublimity. The Countach bears all the design hallmarks that we have come to recognise as a ‘supercar’. A shape defined by its girthy longitudinally-mounted engine with a more racecar-like packaging. Now, this looks like a proper supercar. The Countach is the true Genesis. The beginning of a new era.

The sea changes the Countach introduced is evident when one looks at Walter de Silva’s faithful 40th-anniversary tribute to the Miura. Though just as arresting in its beauty to the original, Lamborghini management passed on the 2006 Miura concept, saying that it doesn’t fit its future design direction.

Rather than harking to past glories, Lamborghini’s future would come in the form of the limited-edition Reventón a year later. Its melange of streaks and angles inspired by modern stealth fighter jets rather than the jet-set lifestyle. A car that couldn’t be any more different than the elegant Miura.

Even though critics lavished the Miura concept with praise, there is no denying that it looked like it was from another era. One that was neither ahead of its time nor fit in with the current supercar expectations. The original Miura certainly was a product of its time. A beautiful product, but one of a bygone era nonetheless.

So maybe Setright was right when he first saw the Miura. He could see the concept for what it would lead to, everyone else just got the wrong car in mind.