If you drink from the Porsche mythos well, there are only two things on the calendar that matters. The launch of a new 911, and the launch of its GT3 variant. The rest might as well be white noise echoing out into the void. And so, here we are in what would have been Geneva Motor Show season getting excited over the new Porsche 992 911 GT3.

For the last two decades, the Porsche 911 GT3 series has always been Porsche’s track tech demo for the road. As expected, the Porsche 992 911 GT3 is a love letter to its fans. Because it isn’t just sprinkled with motorsports inspiration, but drips with race car DNA.

Because racecar

Where to start? Well the engine obviously. No spiced up 911 Carrera engine here. How about a 375kW 4-litre naturally aspirated flat-six with a stratospheric 9000rpm redline? An engine that Porsche claims is “virtually identical” to that used in the GT3 Cup race car.

Then there is the front double-wishbone suspension setup. Lifted from the 911 RSR race car, it represents a milestone for a road-going 911 and a huge production challenge. And finally, there is the new “swan neck” rear wing and diffuser, borrowed from the 911 RSR.

Even for a 911 GT3, that is a lot of “race car-inspired” bits and bobs. But of course, this being an all-new 911 GT3, it seems as though Weissach didn’t hold back. Especially with the current 992-generation 911 Carrera being so good and capable already. So, out with the big guns it is.

In particular, that swan neck rear wing. Big wings have been part of the GT3 recipe, but this new design shows that Weissach isn’t messing around with the Porsche 992 911 GT3. Unlike the GT3 RS’ item, this rear wing isn’t as wide as the body, propped up on spindly thin cantilever struts. But it is the most extreme iteration of a rear wing. Further proof that aerodynamics are taking centre stage in the design of performance cars.

What is this swan neck wing?

To many, the swan neck rear wing looks to be the mad imaginations of modding idols Liberty Walk. But that assumption couldn’t be further from the truth. Instead, the swan neck wing owes its existence to endurance racing development.

Wind the clock to 2008. The organising body of the Le Mans Series, the Automobile Club de l’Quest (ACO), was busy introducing regulations to prevent “yaw-induced blow over incidents”. What is that you say? It is when the quest for aerodynamic gain leads to some really horrific flights of fancy. The most infamous of which is the unintentional “Flying Arrows” that were the Mercedes-Benz CLR.

While the ACO introduced many regulations to curtail such extreme aerodynamic anomalies, reducing cornering speeds was also on the agenda. To achieve this, the 2009 regulations stipulated a reduction in the rear wing’s width from two meters to 1.6.

Cleaning up the design

With less surface area to play with, the new rear wings couldn’t produce as much downforce. Rough estimates saw around a third of its rear wing downforce gone. Of course, teams weren’t going to take the changes lying down, so aerodynamicists began experimenting with aggressive wing angles and profiles.

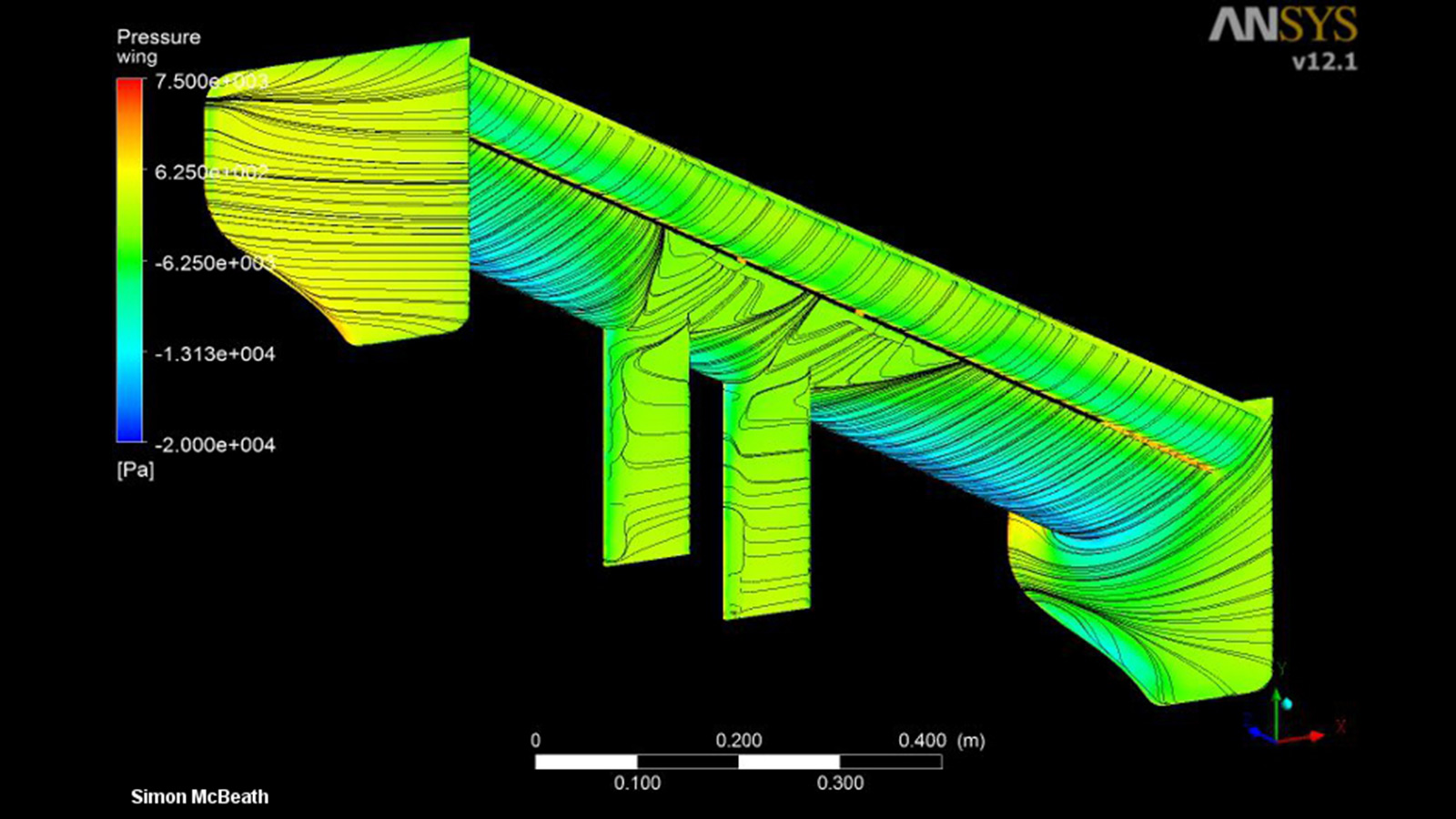

By dialling in a more aggressive rear wing angle, aerodynamicists were surprised that the smaller wings generated even less downforce. They soon suspected that the wing mounts were the real culprits. By standing in front of the wing, these pillars caused what was known as “flow separation”.

According to traditional wisdom, to get more downforce you need a more aggressive wing angle. However, that, in turn, meant the rear wing would be more susceptible to the quality of the airflow beneath it. In the case of the conventional bottom wing mounts, it was splitting the airflow and causing a disturbance in its wake. This small disturbance became more amplified with the aggressive wing angle.

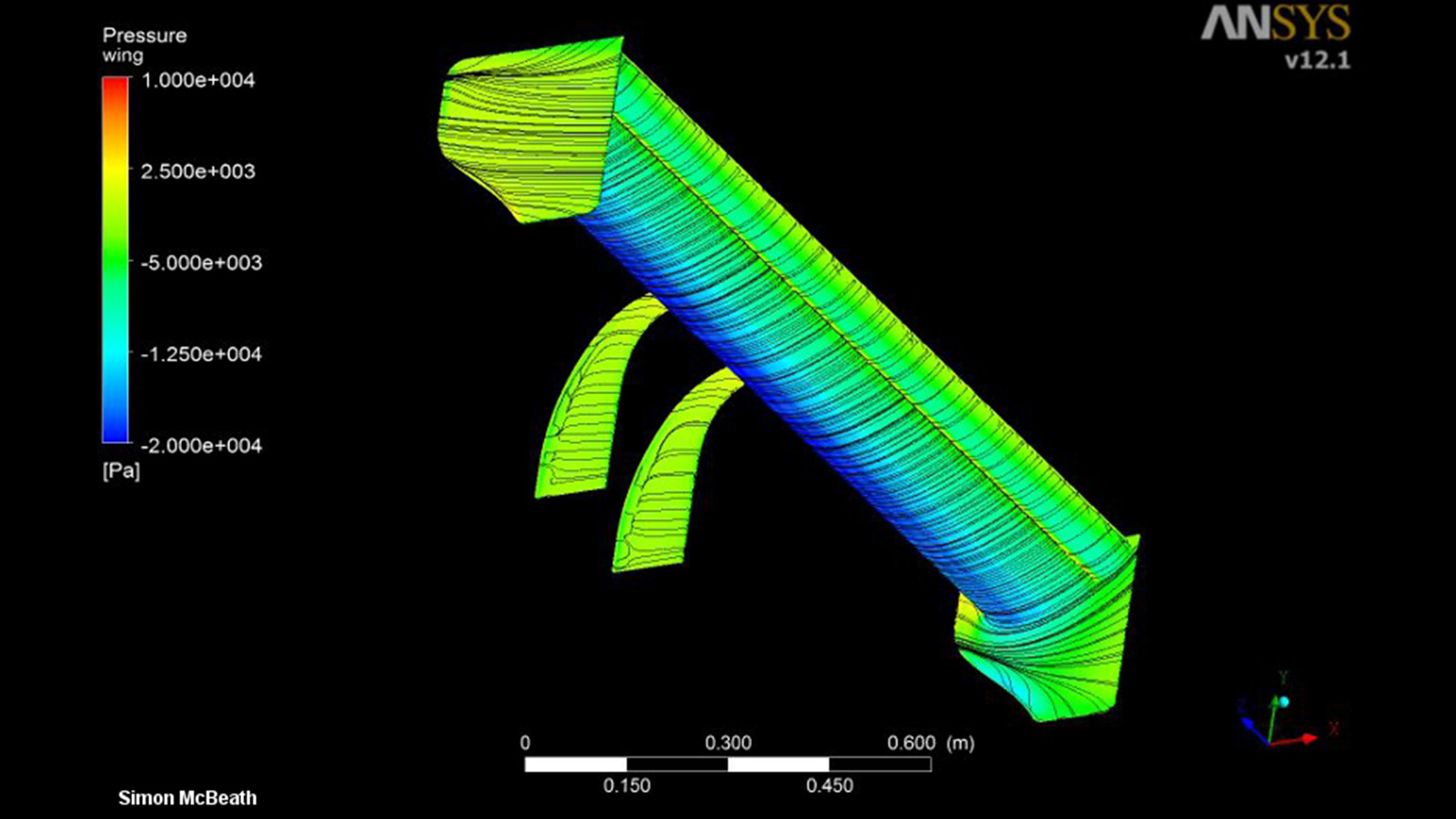

The solution? Get the wing mounts as far away from the underside of the rear wing as possible. Hence, the swan neck design. Aerodynamicists were not only able to eliminate the troublesome flow separation, they also recovered much of the downforce.

According to Mulsanne Corner, it wasn’t just one team who started exploring this novel idea. Both Audi and Acura came to the same conclusion ahead of the 2009 season. Shortly thereafter, the swan neck design became a fixture in motorsports amongst endurance racers, touring cars, and time attack monsters. Sooner or later Porsche was going to adopt it for its road cars, and there is no time like the present.

Porsche 992 911 GT3 – Taken to the extremes

The mass proliferation of race car components and technologies in the Porsche 992 911 GT3 demonstrates the extent to which the upper echelons of performance motoring have risen. Porsche themselves boast that the 911 GT3’s rear wing comes with a “performance position” that “is not intended for street use”. In the said setting, the 992-gen GT3’s downforce gains over its predecessor go from 50 per cent to a whopping 150 per cent.

What is the average 911 driver going to do with that much downforce? Beat tunnel traffic by driving on its walls? Maybe that is the reason why Porsche doesn’t want you using it on the street.

Nevertheless, all this is just tasty morsels to add to the conviction pie to tempt Porsche enthusiasts over the already excellent Carrera models. Which begs the question, just how extreme will the boys at Weissach take the 992 911 GT3 RS? At this rate, they might as well roll out that 919 Street concept in its place. Don’t back down, go the whole race car for the road shtick and own it. Goodness, we could use a new date in the calendar to look forward to.