I know the following sentence is challenging for anyone with an ounce of petrol in their veins. But for a moment, turn your baseball caps forward and put down that can of Red Bull. When I mention the word ‘Mitsubishi’, you need to forget about forest-blasting Evolutions and desert-conquering Pajeros. Got it?

So, what is Mitsubishi good for? No, forget about those things that go fast on dirt. Those memories are mere distractions from discovering the heart of a remarkable company that the world is losing.

If you aren’t aware, Mitsubishi is pushing ahead with its plans to exit from the UK market, even though its Renault overlord will be keeping a vestigial operation in the greater Europe to create French jobs.

Heading to greener pastures

For many, its exit is not surprising. For the Japanese automaker, South East Asia is where the money is at. Not only that, despite focusing on SUVs, the SUV-mad market isn’t responding as well as hoped.

Nobody really knows what to make of the Eclipse Cross. European bureaucracy’s distaste for diesel has put the L200/Triton pick-up truck and Shogun Sport/Pajero Sport’s time on notice. And the developing market developed Mirage really shouldn’t have even stepped foot in Europe.

That leaves Mitsubishi high and dry with the reliable and ageing ASX, and the Outlander. Both are middling SUVs that serve a more rational and utilitarian audience. But nothing worthwhile to go into a song and dance for. That is, except for one lone variant that has become emblematic of Mitsubishi’s strengths and missed opportunity – the Outlander PHEV.

Mitsubishi’s underrated gem

It may not look like it, but the Outlander PHEV was the bravest thing Mitsubishi had done since the 3000GT. And the 3000GT was born from an era of unprecedented excess and optimism.

Out of the blue, just a year after the Chevrolet Volt, Mitsubishi burst on to the stage at the 2012 Paris Motor Show declaring that they will put the Outlander PHEV into production – the first production plug-in hybrid SUV in the world.

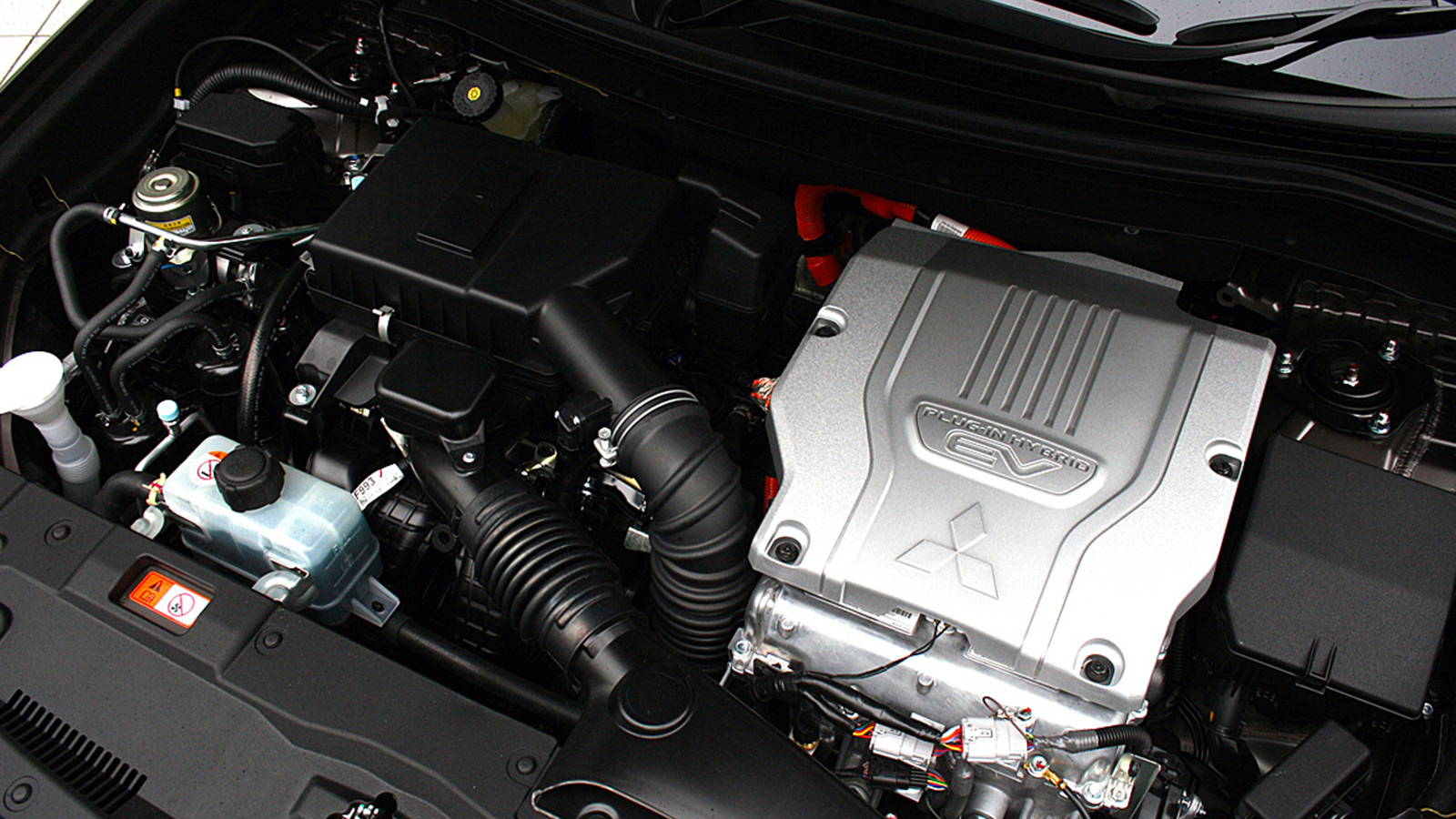

Like the Volt, the Outlander PHEV is predominantly an electric car with a plug point that can feed the drive battery. It does have a four-cylinder engine, but that is there to help the battery when it needs an extra poke.

Unlike the Volt, it came in the shape of a contemporary SUV with its size and barn house-like aerodynamic efficiencies. And because of its shape, there was a fair amount of scepticism of Mitsubishi’s intent to create a frugal fuel saver. But at the end of the day, it had the right stats.

It wasn’t just its SUV practicalities and affordable pricing – for a plug-in hybrid – that made it a tempting proposition. Government incentives and penalty-dodging emissions strengthened its appeal, especially amongst fleet owners.

Plug-in success

All things considered, at its launch, the Outlander PHEV was in a league of its own – even in sales. Unlike its gravel-flinging performance brethren, this unassuming plug-in hybrid SUV actually flew off the dealer lots. From 2014 to 2017, it became Europe’s best selling plug-in electric vehicle, beating out all the popular battery-electric cars.

Even today, with so many plug-in hybrids and all-electric options in the market, and a replacement due, the Outlander PHEV is still generating six-figure sales. As an affordable mid-size plug-in hybrid SUV, its proposition is hard to match. Never mind even beating it.

The amazing thing about the Outlander PHEV is that Mitsubishi hadn’t done anything quite like it before. Its only prior experience in production electric drivetrains was the niche i-MiEV, from which it borrows its electric systems. To transition into the mainstream market so quickly was a measured gamble for Mitsubishi.

Mitsubishi missed chance

However, despite the Outlander PHEV’s success, Mitsubishi never capitalised on the formula. Sure, it created a lot of concepts that toyed with the PHEV idea. One of which was a concept for a possible Pajero replacement. But nothing came of it.

Rumours have it that a new PHEV-equipped Pajero is in the works. Though it is uncertain if Renault-Nissan’s insistence that Mitsubishi adopt its platforms for future models would kill the idea altogether.

So far, the only other model to get the Outlander PHEV drivetrain is the recently introduced mid-life facelift Eclipse Cross. Furthermore, with Mitsubishi shunning sedans and retreating into budget-conscious developing markets, there won’t be many candidates for its plug-in hybrid system. And that is a shame for one of Japan’s brightest automotive luminaries.

The famous LJK Setright, in his final column for Car Magazine in 1999, described Mitsubishi as “one of the cleverest in the world and probably second only to Honda”. Mind you, the Honda of Setright’s era wasn’t building family-friendly SUVs or the long-wheelbase City. This was the radical ‘Big H’ when it was led by a genuine mad lad who experimented with jetpacks.

Yes, Setright might be a bit of a free-spirited contrarian. And his particular column was referring to Tommi Makinen’s third consecutive WRC Driver’s title with the Mitsubishi team. But he lived through an era that demonstrated Mitsubishi’s engineering prowess outside its motorsports exploits.

Glittering history of Mitsubishi

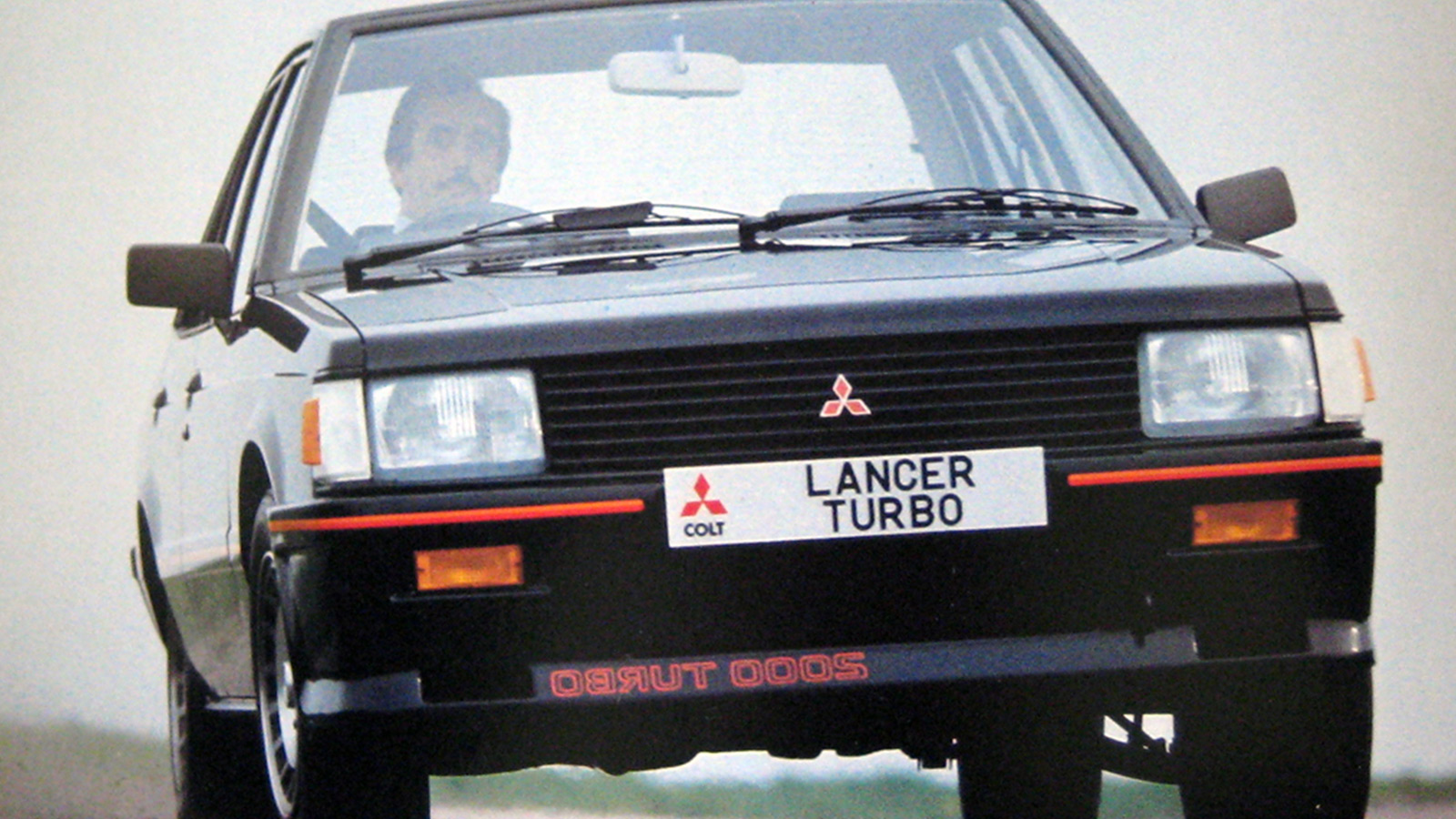

The rise of Mitsubishi Motors began in the 1970s. A time when it made a name for itself with solidly built cars like the Colt Galant. The company followed Saab’s lead and adopted turbocharging for its road cars, with the Lancer 2000 Turbo and Starion in the following decade.

Cars aside, Mitsubishi also made its mark was in the off-roader space. The 80s saw the birth of the beloved and durable Pajero off-roader. Another Japanese SUV that further squeezed Land Rover’s diminishing market share.

Not satisfied with just having the Pajero, Mitsubishi’s engineers carried over its drivetrain to the Delica MPV, creating an overland camper van that was decades ahead of its time.

Mitsubishi’s advanced and troubled 3000GT wasn’t the only boundary-pushing creation of the 1990s. Its Japanese-market eighth-generation Galant boasted the world’s first mass-produced direct-injection petrol engine. Even less known was its third-generation Debonair flagship that had self-closing doors and a world-first Lidar distance detection system.

Though the Japanese asset bubble pulled the rug from its feet and deflated its risk appetite, Mitsubishi did pull some surprises in the noughties, the most notable of which was the i Kei car. A car that Setright might have approved of.

The Mitsubishi i was unlike any Kei car that came before, even by the standards of Japan’s bubble era. Though conceived as a compact runabout for families, Mitsubishi shook up the formula with a mid-rear engine and rear-wheel-drive layout that maximised space in a car with zero overhangs.

It worked. Mitsubishi little i became a hit in the domestic and international market, earning multiple awards and becoming the platform for its first production all-electric model, the i-MiEV.

Faulted to falter

Criticise Mitsubishi’s track-record of lacklustre design and less-than-impressive interiors all you want. It is undeniable that it is one of the few companies that prioritise engineering, even to a fault.

While it had its engineering part of the business nailed down, Mitsubishi kept botching its business strategy. For reasons that aren’t understood, the automaker kept running into a series of bad business decisions and unfortunate circumstances.

From a troubled partnership with Chrysler to an aborted Australian sedan and the Asian financial crisis, one would think that Mitsubishi was a magnet for misfortune. None of which was as damaging as the double squeeze from the mid-2000s commodities price boom and environmental legislation.

During that period, Mitsubishi busied itself with electrified drivetrains. Credit where it is due, that is forward-thinking. However, it was myopic in its approach, leaving its near-term plans hinging on outdated powertrains and platforms. This left it vulnerable to the immediate changes in the marketplace, especially when it came to downsized and diesel-powered engines.

To plug that gap, Mitsubishi tried desperately to cross-match models into markets where they don’t belong. And no model demonstrated this better than the sixth-generation Mirage.

Developed to take advantage of Thailand’s Eco-Car policy, the Mirage hatchback was ideal for developing markets. And it should have stayed there. Instead, Mitsubishi thought that it could cut it in demanding markets like North America and Europe. It didn’t. And like a roadside explosive, it spectacularly bombed and took down all the goodwill around the Mirage name.

A beacon for an uncertain future

While Mitsubishi boasted of grand plans to roll out a whole range of new models to address all these issues, a fuel efficiency scandal in 2016, ultimately killed its dreams. Nissan circled in to pick up the scraps and incorporate the company into the giant Renault-Nissan alliance.

The new alliance made Mitsubishi a part of the world’s largest automaker. Initially, there were promises that the new arrangement would help the storied name gain some of its footings back. Unfortunately, just a year after its formation, the alliance tripped over itself due to its own internal politicking.

Today, Mitsubishi is relegated to the unfortunate third wheel as Renault and Nissan continue to fight their fires in its home markets. At this point, nobody is sure if Mitsubishi will return itself to prominence. Hopeful platitudes are still trumpeted in front of investors, yet no firm commitments are made.

Hopefully, that “Three Diamond” logo will stand for some resilience, even if it barely glitters nowadays. Till that time comes, Mitsubishi’s stewards would do well to learn from the success of the Outlander PHEV.

It might have looked like a frog, but it was a revealing moment of gallantry on Mitsubishi’s part. It saw an opportunity, leapfrogged the market, and defined a niche. If Mitsubishi can catch lightning in a bottle as it did with the plug-in Outlander, as it has done so with many of its models, then we can get around to talking about its rally heritage again.