To paraphrase a quote from Mahatma Gandhi – ‘I like electric cars, I do not like electric car advocates.’ I’m sorry, but there is just something insufferably sanctimonious about electric car fans. It is as though they are better than you. Well, they aren’t. There remains a price to pay for one. On the forecourt and in the business of lithium mining.

Most of the public discourse on the environmental merits of electric cars focuses on their power sources. To my understanding at least, that point is moot. Electricity generation is getting cleaner, and distributing it is far more efficient than sending it on sea- and road-going tankers.

Why nobody cares about lithium mining

Curiously, nobody on either side of this debate seems bothered by the ethical price we pay for extracting lithium. Of course, to the public, lithium mining is as environmentally ambiguous as iron ore, oil, or diamonds. It is bad, but it is a necessary evil to ensure an environmentally secure future. Also, environmentalists need batteries too. How else can they virtue signal on the internet?

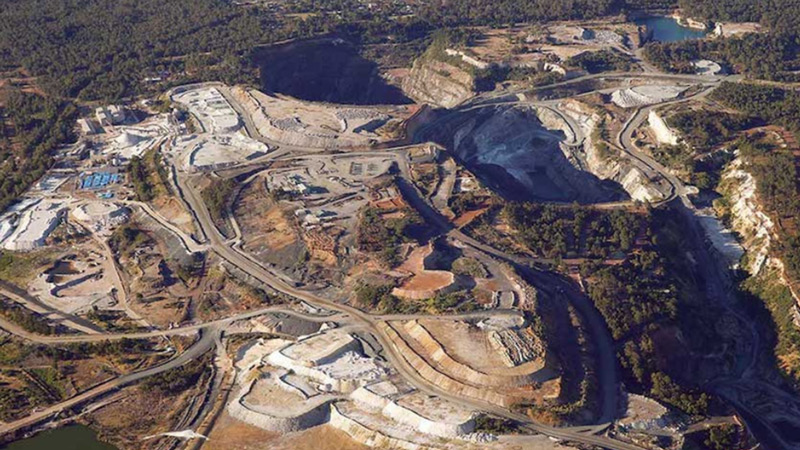

This generally apathetic attitude shown towards lithium mining has much to with the location of these mines. Most lithium mines are in remote, unpopulated regions far from population centres. Out of sight, and usually, out of mind of most city dwellers and environmental lobby groups.

A convenient oversight for many electric car advocates. Lithium mining, be it from hard rock mines or extracting it from underground salt reservoirs is extremely energy and water-intensive. Researchers estimate that hard rock mining produces 15 tonnes of CO2 for every ton of lithium. Salt reservoirs are that much better either. Though producing a ton of lithium only releases 5 tonnes of CO2, extracting it from salt flats would consume nearly half a million litres of water.

Beyond the numbers, lithium mining isn’t environmentally responsible either, as there have been reports of water shortages and contamination. Though it can be argued that these cases occur in regions where government oversight is a little ‘flexible’.

To their credit, car manufacturers like Volkswagen try to be mindful of where the lithium in its batteries is coming from. Adding to that, it isn’t as though the business of oil extraction has had a spotless history. It just had the industry’s processes and efficiencies have decades of development behind it.

Geothermal breakthrough

More recently, mining companies have been exploring the possibilities of extracting lithium from underground geothermal brine. According to consultants, the process is far less resource-intensive and environmentally damaging. In addition to that, the geothermal energy from the source itself could power the whole operation.

Recently, geologists have found one of the world’s largest deposits of lithium in geothermal brine. According to their estimates, there is enough white gold in it to equip more than 400 million electric cars. Thing is, the deposit is in Germany and not just any part of the country’s 357,000km2 land area, but right in its Upper-Rhine valley.

Considering the growing movement to ban the sale of fossil-fuelled cars across Europe, couple to the German car industry’s strong push towards electric drivetrains, Germany would be foolish not to tap its lithium deposit. What’s more, as a pandemic, national security concerns, and a stuck ship, have demonstrated, local sourcing is the safest bet.

Last year, German car manufacturers imported 5300 tonnes of lithium. According to the German Mineral Resources Agency, the country’s lithium demand will rise to 9000 tonnes if electric car take-up is slow, and 32,000 tonnes if it isn’t. Estimates of an Upper-Rhine valley mining operation place a production rate of around 15,000 tonnes by 2024. Comfortably enough to support a burgeoning industry.

The politics of lithium mining

However, the question for Germany isn’t so much a financial one as it is a political one. In countries like China and Chile, lithium mining activities have resulted in grievous environmental damage and pollution. Often, these activities are only possible due to a lack of government oversight or bureaucratic apathy.

Pro-clean energy nations like Germany never really had to deal with these issues, to begin with. From their standpoint, these materials come from far away lands, from so far down the supply chain that accountability becomes vague. But how will Germany react if a lithium mining operation opened right in its heartland? Not only that but in a historically and culturally significant area like the Upper-Rhine valley?

On the plus side, geothermal brine is far less environmentally scarring and resource-extensive than its other methods. However, it is very energy-intensive, which is worrying for a country becoming increasingly dependent on its neighbours for power.

Furthermore, in 2007, geothermal drilling near a village in the Black Forest resulted in several houses being lifted and damaged. With such a precedent, miners are expected to face an uphill task with increased scrutiny.

Embracing the necessary evil

Can Germans stomach the idea of a potentially damaging mining operation to mar their beautiful land? But why should the burden of creating the materials to save the world rest solely on less fortunate nations? And to refuse the opportunity to extract lithium would be a morally hypocritical stance for a nation like Germany.

Chances of that happening are unlikely with rising demand expected in the coming years. Not only that, but the World Bank estimates that the world needs five times the amount of lithium that is currently mined to meet its global climate targets by 2050. So there is an impetus.

For now, lithium mining operations in the Upper-Rhine valley region hasn’t got the go-ahead. Feasibility studies are still ongoing with a decision to be made sometime in the middle of this decade.

When the time comes, it would be interesting to see where the lines are drawn on the debate for the resource. Fittingly there is an appropriate word to describe Germany’s quandary that originates from there. It’s called Schadenfreude.